At the end of my father’s life, in nearby Mougins, the doctor came in with some bleak news. The family was all standing around. My Dad listened, his eyes open. On hearing the bad news, he turned to us and said, slowly, “Can I have a Coke?” And we said “No.” Then he said, “Well then… how about a soda?”

I want to thank you for coming – from the four places he loved the most: Romania, America, England and France. Thank you Father Matthieu. Thank you Father Radu for being with us. My mother, Nick, Radu and Sandra are deeply grateful.

Good to see such a full church. It would have been even more full had not my father outlived so many of his friends. Nick said last week, “It’s funny that all our friends knew Dad. But we did not know our friends’ dads.” He was like CS Lewis, a tutor at Oxford, forever young – and that’s one reason why our friends loved him – he was forever young. But that is not the only reason we’re here. Look around in this church, the very church where over the expanse of 30 years, parting words have been uttered for his mother, his father and his brother Teddy.

In these walls are so many of the people he loved. He appreciated loyalty – and by your presence, you show your loyalty back. Each one of us had our Radu stories; we traded them around in calls and emails. We all wanted one more.

I see Tobias Suttle from Maine with whom he wanted to take a last boat trip down the Danube. And there is Edouard Prost who he helped dodge the French draft in Boston and get a job at Mass General Hospital. And the Keefe brothers who for decades made him laugh and laugh and laugh… and when he was sick, would sooth his mind with their medical knowledge. And there are others, who are not here, like Bill Maloney, one of his best students. Bill wrote me recently, “Even for those who fell short of his high academic standards, you suffered no rebuke at all – but only encouragement and yet further assistance.”

He helped us without taking credit for it, or thinking he was doing us any big favors.

Because there are children here – and more than a dozen Florescu children- people really who have more years to live than years lived, I want them to understand what their grandfather did.

He was born in Bucharest on October 23, 1925, and was educated mostly by tutors. By age 16, he spoke four languages and had already developed his taste for history. At Christ Church, Oxford, where, as a student, he worked under AJP Taylor, the Regius Professor of History at Oxford, and William Deakin, Winston Churchill’s biographer, he received the Gladstone Historical Prize. He started his academic career at University of Texas, then Indiana University where he got his Ph.D., and finally to Boston College, where, over a near half-century, he moved from Lecturer to Professor Emeritus.

As a professor, he won a Fulbright Scholarship, an American Philosophical Grant, a Ford Foundation Grant, and an IREX grant. In 2000, he was inducted as Diploma Honoris Causa in the Romanian Academy. He oversaw scores of doctoral students in Romanian history — a comet’s tail, to use a description of by one of his students. Today, that tail of professors stretches from California to India. They now teaching Balkan history to thousands more.

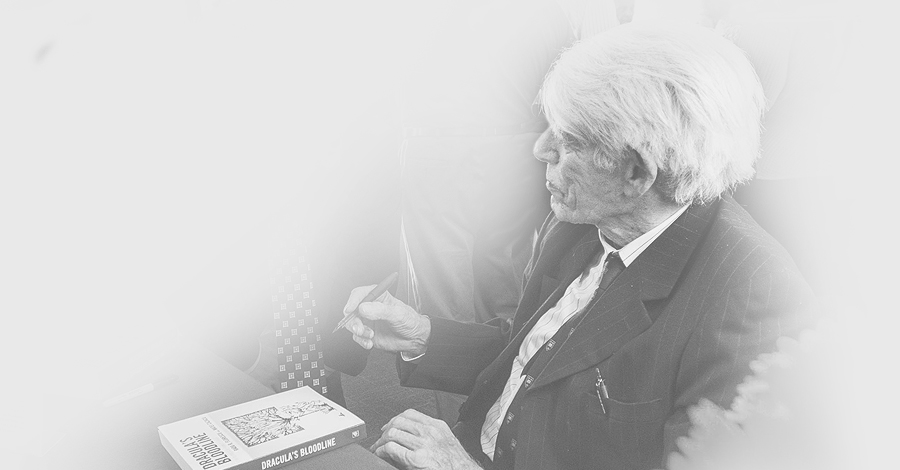

He wrote 13 books — six on Vlad Tepes in which he debunked the Dracula legend and presented the real Vlad Tepes to the world. He wrote more than 60 academic articles, and his work was the subject of documentaries on the BBC, Discovery Channel, History Channel, ABC to name just a few. He started two charities and helped sponsor more than 50 gifted Romanian kids to study in the Boston area.

He served as an advisor on Romanian affairs to the US State department and to the late Senator Edward Kennedy. On the occasion of Romania’s induction into NATO in 2004, he was invited by President Clinton to attend the White House ceremony. He achieved public recognition only after the hard work was done.

At age 88, he was the longest surviving male on record in our 700-year old family. We cannot feel cheated.

My father loved life – cars, boats, all things Romanian, tending the flowers with Ali, dogs, and politics, walks along the Croissette, the Glades and Provincetown, tailored suits, his students at BC, tennis and the Romanian kids, visiting Yvonne at Minster Abbey, writing in Poiana-Brasvo with Ildiko nearby, and always driving to the “next place.” Dan was always there to drive him. “Why don’t you take a plane, Dad? “ He’d say, “ What’s the rush?”

Because we knew him familiarly as Dad, or Uncle Radu, the Big or Doo, you never thought of his life to be a grand adventure. But in fact it was – history made it so.

As a boy, he could remember arriving by horse carriage for weekends in the countryside in Copaceni. There, over-paid tutors would ask Yvonne, his sister, during exam week questions like, “Yes or No.. Do cows have feathers.?” He could tell you about the neighbors, the Goerings – as in Herman Goering, the head of the Luftwaffe – who lived down the street in pre-war Berlin. His German nannies tried, unsuccessfully, to teach him to ‘heil Hitler’ the dictator as he was driven by. He once saw his father mistaken for a Jew and detained by Nazis thugs.

He could tell you about how – at age 13 on orders of his father who was working as a diplomat in faraway London – he boarded one of the last Orient Express trains out of Romania before Europe was divided by Hitler’s aggression. He could tick off his wartime duties – such as all night vigils atop Tom Tower at Christ Church to scout for German bombers — or recall listening to George VI, the King with the speech impediment.

Five years later, with our mother-to-be, he would board a lowly cargo ship- a John Deare cargo – from Southampton to New Orleans – with no money and not much support. His first steps in academia were at the University of Texas. Later, after Sam Rayburn got him his citizenship, he would become a best-selling author, a mini-celebrity to millions of Americans.

Repeatedly, he would return to his Romania, the homeland he loved unconditionally – with or without the Communists. When we visited Communist Romania, he would tell us the stories of our family while we stood outside the fences of our former homes.

And shortly after Ceausescu was executed, and the Revolution declared, he would read — on national TV — an open letter from Senator Kennedy to a now- freed Romanian people.

Little wonder that Radu Florescu, Sr. became a historian. He always felt that the study of history allowed him to reunite the two sides of a world – Romania and the West — severed by a World War. Beyond the monarchy that he trusted – he saw his native country survive the three “isms” of his century – fascism, communism, and a cobbled-together sort of capitalism.

All this sounds like pages from an old history book. Yet it was his life, a life filled with courage, sacrifice, and purpose.

He had his faults, no doubt. He questioned Mariana, his ever-loyal nurse and friend to the end, whether he would go to heaven. “Is vanity a sin?“ he once asked. I don’t know if he was confiding anything in me but one day he asked, “I wonder if it is a big sin to have lied to insurance company about the car accident.”

Dad was an atypical father – a bit of an eccentric himself.

We all know he suffered from Romanianitis – the adoration of – and forgiveness for- of all things Romanian.

The burden imposed by of Romanianitis fell mostly on my French mother. “Non pas encore des Roumains!” It’s not like my mother didn’t like Romanians. She had plenty of Romanian friends herself – many in the church here. She just wanted to see other nationalities from time to time.

My father is living proof that the apple never falls far from the tree. He had his father’s morality and sense of family, his mother’s style and humor; his brother’s tireless drive. And his sister’s kindness and eccentricity. When I asked his Sister, a Benedictine Nun, to come quickly to Cannes for the end was in sight, the first thing she said was, “I have to check with the ducks.”

In our family, my father was the oak tree. Each member had a hand on the trunk – and through him, on his native Romania. He would always ask, “How are things in Romania?” …And only after then, “How is our business?” He never moralized. When little rubs jolted family harmony, he sought to sooth them. He would be quick to apologize and taught us to forgive.

This old world gave him old values, and long-gone, style – gentlemanly, unhurried, elegant, modest and a times hypocritical in that pleasant sort of British way. I too regret much of the world that departs with him.

I remember at a small dinner party with Francis Ford Coppola. My father said, “I love your movies.” Coppolla said, “Which ones did you like?” My father paused and said, “Which ones have you done?” Coppolla said, ” Godfather 1 “ My father said “Didn’t see that one.” “ Coppolla added, “Godfather 2.. “No I missed that one too. “Apocalypse Now.” And so it went on with absolutely no offense to the legendary director.

Another day my mother called desperate. “ Votre pere a oublie de tirer le frain a main. “ And the car rolled down the hill into the ditch. My father said nothing for two days. Two days. Then he called me, “You know I met a charming Romanian tow truck operator today.” He never mentioned the accident. He later told to Dan, “I didn’t like the car that much anyways.”

I remember the fiasco when he stayed, alone, at Eugene Ionescu’s apartment in Paris in the 1970s. One morning, dressed only in his underpants he stepped out into the hallway to grab the newspaper. To his horror, the apartment door slammed shut behind him … and locked. Almost nude, with the paper, he had to knock at the French neighbor’s door, “Pardon Monsieur. Vous avez le clef de l’apartement de Monsieur Ionescu?” The French neighbor must have thought he was watching a play of Ionescu.

My father liked people high or low. A college friend, Abera Kassa, nephew of the Emperor Halie Salasie , “the Lion of Judda,”– imagine on a business card, “Lion of Judda” – now a poor immigrant in the US, no job. It was almost a joke, but not for my father. He knew the tricks history could play on a family and he took him in his home for months, and then helped his children. My father had time and pleasure for the less fortunate: I can think of some of his closest friends who never finished high school or found themselves in subsidized housing.

He finally left America in part because he was mad at Massachusetts “They took away my driver’s license.” Can we call Senator Markey? You know he was my student…’ he said. He then laid his out case: “I am one of the best drivers I know.” When WE said we could not undo the law, my father changed tactics, “My ears work better when I drive the car.”

One of his final ambitions was to renovate the monument in Calugareni, near Bucharest, where his ancestor and namesake Radu Florescu fought the Turks in 1595. He wanted one of his grandchildren to follow in the footsteps of Nicolau Melescu, a Romanian aide to Peter the Great to retrace his great road trip to China. He wanted my son Peter to write a children’s book, predictably entitled, “I have a Little Dracula Bone in My Body.”

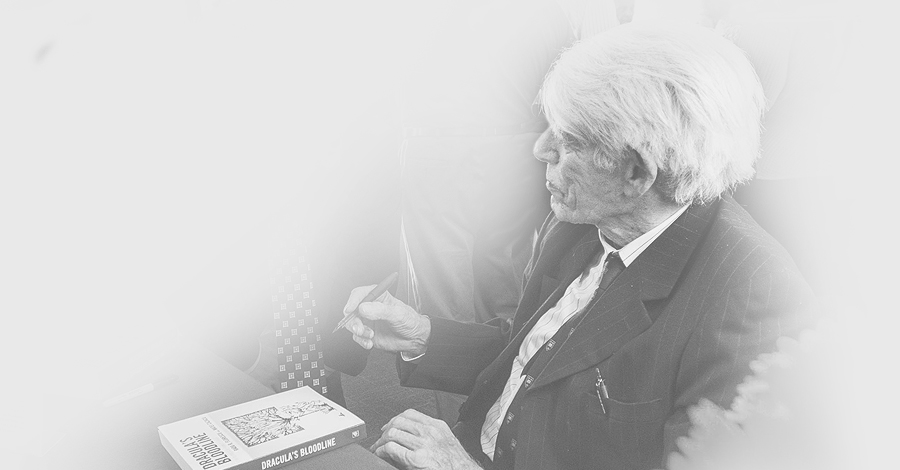

He asked Mariana to buy a new ribbon for the typewriter. She went everywhere around Cannes to find that near-extinct commodity. When she found it, and wedged it in to the typewriter, it still didn’t work. Only then did we realize that my father no longer had the strength to strike the keys with sufficient force to make an imprint on the page.

When he could not write any more, it was the beginning of the end. “John, I can not read, I can not write, I can not walk. What purpose is my life?”

He expressed five wishes before he died. His mind was clear. After each wish, we would repeat his exact wish back to him. He would nod as if to confirm. : Take care of your mother. Look after everything about Romania. Keep United as a family. Look after my sister and, Look after my books. Perhaps the most moving site for me was what I saw between my mother and father. The journey had been long, sometimes hard, but in the end all was either forgotten or forgiven. And only love remained. On his death bed, my mother sang into his ear his favorite song – Charles Trenet’s “Mes ta mains dans ma Main.”

In one of the drafts of his family history, he wrote an ending that he never published. In that Epilogue, he talks about how in the Orthodox church, where he and most of the Florescus were baptized, one’s soul is judged by those family ancestors who have gone before in judgment. In Romania, in our family, they are painted on the exterior of the monasteries. The most ancient tombs are at the monastery of Tismana. The second generation are at Gaiseni; and the third at the monastery of Tiganesti. At the end of my father’s manuscript, he writes, and I quote, “ I sometimes I wonder how I will be judged and received in the family fold. I hope that I shall join them, my ancestors, as pictures on the monastery walls in their very earth like Paradise.”

I don’t know if you shall be painted on those walls, dad, but I can assure you that you are on the walls of my heart and all of our hearts, forever.